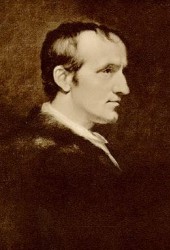

William Godwin [1756-1836] English

Rank: 101

Writer, Journalist

William Godwin was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Independence, Education, Imagination, Brainy, Communication, Courage, Famous, Government, Intelligence, Legal, Men, Patience, Power, Sympathy |  |